I've been thinking...

Very, very few smashers really understand the fundamentals of the Smash Brothers family of games. Sure, vast swaths of text are spouted nonstop from Smashboards' eternal depths about tactics and advanced techniques, but these are not fundamentals. They are tools which are useless without fundamentals. If you don't know what a hammer is good for, why even know how to swing it? I've felt a strong aversion to this obsession with finding advanced techs and little shenanigans like they're actually going to change what everyone is fundamentally doing in the game for a long time, but I never really understood why until recently. This is because in a way I had bought into the notion that ATs and situational tactics were what the game was all about. It wasn't stupidity so much as ignorance. I didn't know any better, and that wasn't really my fault.

The foolhardy focus on ATs and clever tactics is terrifyingly pervasive in the Smash Brothers tournament community. I have been a part of this community for nearly four years, and I didn't even realize I didn't know the fundamentals of Smash until I started playing other fighting games, like Guilty Gear, BlazBlue and Street Fighter. I didn't realize it was a problem until I started following and commenting on TheBuzzSaw's project, Zero2D. There wasn't really anyone in the community talking about what the fundamentals of Smash are. Plenty mentioned their existence, but they were all tight-lipped as to what the fundamentals were. Maybe they knew these basic truths intrinsically, but couldn't put them into words (I suspect most of the best fall under this heading). Maybe they assumed that everyone understood these basic facts, and didn't feel the need to elucidate. Maybe they were big jerkwads and didn't want to talk to the rest of us about it, because they wouldn't have that advantage. I don't know, and I don't particularly care. The fact is, I learned about Smash Brothers in a poisonous environment that taught me, effectively, nothing about the game. I was swinging a hammer at air.

Like I said earlier, I didn't realize I didn't know what I was doing until I started playing, and reading about, other 2D fighting games with well-established communities and metagames. Oddly enough, it wasn't even the communities that I learned the game fundamentals from; it was the games themselves. The fundamentals of these games are just that in those communities: fundamentals. People talk about the game in terms of these fundamentals. I couldn't make heads or tails of what they were saying until I actually played the games. That's when I realized what an overhead was, what a wake up was. Any time someone said something along the lines of, "I have found this technique that allows you to follow up with either an anti-air or a command grab," it was like a hammer that came with a little drawing of someone using it to nail two planks of wood together. I began to realize that I didn't have an instruction manual like that for Smash. Not even the How to Play video gave a whole lot of insight into this. The gist is, these games have fundamental rock-paper-scissors relationships between various aspects that underpin every decision the player makes.

I'm not going to get into the entire RPS system of your standard 2D fighter here. I've tried doing a flowchart just of move classes, and it was a veritable Gordian Knot, and this was without taking into account cross-ups, zoning, option-selects and any number of other fundamental system functions. Let's just look at the relationship between two options: blocking low and the overhead. Blocking low is typically a good decision when under pressure in a lot of fighting games, at least BlazBlue and Guilty Gear, my knowledge of SF being more nebulous, but considering how often I see players blocking low in that game, I'm assuming it's no bad idea. Anyway, Blocking low is strong because most quick attacks are either lows or mediums. Aerials beat low blocks, but since most anti-airs (which beat aerials) are fairly quick, lead to a lot of damage, and involve the crouching motion in some way, aerials usually aren't a great decision. Usually. Another way to beat the low block is with an overhead. Overheads typically aren't super-fast, but they're faster than most aerial options, and aren't any more weak to anti-airs than any other ground option, and they usually lead to combos as well. An overhead's biggest weakness is blocking high. Usually, overheads are difficult to follow up on block, so a successfully blocked overhead is usually a good thing for the blocker. Since they're pretty good for starting combos, but fairly easy to punish, this presents the player with a trade-off. Trade-offs like this ramify throughout the system, and they convolve with other mix-ups and trade-offs. Any competent player of a 2D fighter can tell you about this, even when they play the game casually. But try asking anyone on Smashboards about the analogue in Smash. Most wouldn't know. Some would even get a haughty tone and tell you that Smash is too complex to be boiled down to such simple concepts.

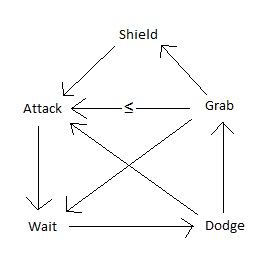

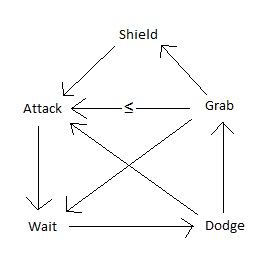

If only they knew. Let's look at an analogue to the above relationship in the Smash system. Namely, shielding and grabbing. Shielding is, overall, pretty powerful in Smash. It deflects almost any attack, and gives ample opportunity for counterattacks. The only actual attack it does not beat is a well-angled and well-spaced shield-poke, but those are difficult to attain, and the rewards are frequently tepid. But what does beat shield, is grabbing. Grabs, like overheads, are typically slower than normal attacks, but fast enough that they're difficult to avoid if you're not paying attention. Furthermore, they typically have a very high reward. On the flipside, grabs are beaten pretty solidly by dodging. But if the dodge is baited and punished, then it doesn't work out so well. Bam. That's a mix-up.

And now here's where you begin to look stupid for thinking Smash is "too complex" for one of those really simple rock-paper-scissors systems. Actually, it's not. The move class flowchart for smash only has about five nodes, some of which don't even really beat each other outright. If breaking even doesn't count, there are eight relationships that actually matter. Compare this to the ten or so nodes of most fighters, with nearly twenty relevant relationships between them, and you can see that Smash is really quite simple when you break it down. I've included this flow-chart below.

Now I tasted some salt earlier. I heard a few voices cry, "But ph00tbag! Everyone knows a grab beats a shield!" Well, yes, they do, but that goes right back to the whole hammer thing, although the analogy is less clean. Essentially, most smashers have the knowledge of these relationships, but they are either ignorant of, or don't care about, their significance. What's significant, is that this is one of the flow charts every player needs to have in their head when playing the game, with frequency tables for everything, and statistical analyses to make sure their findings are significant. The relative strengths and weaknesses of each option needs to be weighed. Two PhD dissertations need to be written out for any given match, one for what's going on in each player's head. If you aren't doing this, even subconsciously, while you play, you are playing the game wrong. Bad competitive players just play safe and don't think about these options, but are able to win a couple matches because they're patient. Terrible competitive players aren't even patient. Neither of these types wins tournaments. So you see, even this knowledge is a tool, and many smashers know the knowledge, but they don't know why that's important, so even if they use the tool, it's like using a hammer to make a moulding. The results aren't pretty.

Ok, so I may have gone a tad overboard with my initial stipulation. It's not so much that no one knows the fundamental system of smash. Get enough experience with the game, and most of the revelations there aren't so revelatory, after all. But players of other fighter communities still get something that a lot of smashers just don't get. They actually worry about their game's systems while playing, even the terrible players. They know that thinking about this is the key to victory. And if they lose, it's because they're just not good enough to extrapolate consistent reads from their opponent. But a good many smashers don't seem to care about that. That needs to change. There need to be more threads that actually lay out plainly what beats what, in a general sense, for a given system, and why the relationship in that system is important. This community needs to be more concerned with what the fundamentals of Smash entail. Hopefully, this essay can cause that change. Hopefully, Smashboards can finally start talking about using those hammers to drive some nails.

Cross-posted in the Brawl Boards.

Very, very few smashers really understand the fundamentals of the Smash Brothers family of games. Sure, vast swaths of text are spouted nonstop from Smashboards' eternal depths about tactics and advanced techniques, but these are not fundamentals. They are tools which are useless without fundamentals. If you don't know what a hammer is good for, why even know how to swing it? I've felt a strong aversion to this obsession with finding advanced techs and little shenanigans like they're actually going to change what everyone is fundamentally doing in the game for a long time, but I never really understood why until recently. This is because in a way I had bought into the notion that ATs and situational tactics were what the game was all about. It wasn't stupidity so much as ignorance. I didn't know any better, and that wasn't really my fault.

The foolhardy focus on ATs and clever tactics is terrifyingly pervasive in the Smash Brothers tournament community. I have been a part of this community for nearly four years, and I didn't even realize I didn't know the fundamentals of Smash until I started playing other fighting games, like Guilty Gear, BlazBlue and Street Fighter. I didn't realize it was a problem until I started following and commenting on TheBuzzSaw's project, Zero2D. There wasn't really anyone in the community talking about what the fundamentals of Smash are. Plenty mentioned their existence, but they were all tight-lipped as to what the fundamentals were. Maybe they knew these basic truths intrinsically, but couldn't put them into words (I suspect most of the best fall under this heading). Maybe they assumed that everyone understood these basic facts, and didn't feel the need to elucidate. Maybe they were big jerkwads and didn't want to talk to the rest of us about it, because they wouldn't have that advantage. I don't know, and I don't particularly care. The fact is, I learned about Smash Brothers in a poisonous environment that taught me, effectively, nothing about the game. I was swinging a hammer at air.

Like I said earlier, I didn't realize I didn't know what I was doing until I started playing, and reading about, other 2D fighting games with well-established communities and metagames. Oddly enough, it wasn't even the communities that I learned the game fundamentals from; it was the games themselves. The fundamentals of these games are just that in those communities: fundamentals. People talk about the game in terms of these fundamentals. I couldn't make heads or tails of what they were saying until I actually played the games. That's when I realized what an overhead was, what a wake up was. Any time someone said something along the lines of, "I have found this technique that allows you to follow up with either an anti-air or a command grab," it was like a hammer that came with a little drawing of someone using it to nail two planks of wood together. I began to realize that I didn't have an instruction manual like that for Smash. Not even the How to Play video gave a whole lot of insight into this. The gist is, these games have fundamental rock-paper-scissors relationships between various aspects that underpin every decision the player makes.

I'm not going to get into the entire RPS system of your standard 2D fighter here. I've tried doing a flowchart just of move classes, and it was a veritable Gordian Knot, and this was without taking into account cross-ups, zoning, option-selects and any number of other fundamental system functions. Let's just look at the relationship between two options: blocking low and the overhead. Blocking low is typically a good decision when under pressure in a lot of fighting games, at least BlazBlue and Guilty Gear, my knowledge of SF being more nebulous, but considering how often I see players blocking low in that game, I'm assuming it's no bad idea. Anyway, Blocking low is strong because most quick attacks are either lows or mediums. Aerials beat low blocks, but since most anti-airs (which beat aerials) are fairly quick, lead to a lot of damage, and involve the crouching motion in some way, aerials usually aren't a great decision. Usually. Another way to beat the low block is with an overhead. Overheads typically aren't super-fast, but they're faster than most aerial options, and aren't any more weak to anti-airs than any other ground option, and they usually lead to combos as well. An overhead's biggest weakness is blocking high. Usually, overheads are difficult to follow up on block, so a successfully blocked overhead is usually a good thing for the blocker. Since they're pretty good for starting combos, but fairly easy to punish, this presents the player with a trade-off. Trade-offs like this ramify throughout the system, and they convolve with other mix-ups and trade-offs. Any competent player of a 2D fighter can tell you about this, even when they play the game casually. But try asking anyone on Smashboards about the analogue in Smash. Most wouldn't know. Some would even get a haughty tone and tell you that Smash is too complex to be boiled down to such simple concepts.

If only they knew. Let's look at an analogue to the above relationship in the Smash system. Namely, shielding and grabbing. Shielding is, overall, pretty powerful in Smash. It deflects almost any attack, and gives ample opportunity for counterattacks. The only actual attack it does not beat is a well-angled and well-spaced shield-poke, but those are difficult to attain, and the rewards are frequently tepid. But what does beat shield, is grabbing. Grabs, like overheads, are typically slower than normal attacks, but fast enough that they're difficult to avoid if you're not paying attention. Furthermore, they typically have a very high reward. On the flipside, grabs are beaten pretty solidly by dodging. But if the dodge is baited and punished, then it doesn't work out so well. Bam. That's a mix-up.

And now here's where you begin to look stupid for thinking Smash is "too complex" for one of those really simple rock-paper-scissors systems. Actually, it's not. The move class flowchart for smash only has about five nodes, some of which don't even really beat each other outright. If breaking even doesn't count, there are eight relationships that actually matter. Compare this to the ten or so nodes of most fighters, with nearly twenty relevant relationships between them, and you can see that Smash is really quite simple when you break it down. I've included this flow-chart below.

Now I tasted some salt earlier. I heard a few voices cry, "But ph00tbag! Everyone knows a grab beats a shield!" Well, yes, they do, but that goes right back to the whole hammer thing, although the analogy is less clean. Essentially, most smashers have the knowledge of these relationships, but they are either ignorant of, or don't care about, their significance. What's significant, is that this is one of the flow charts every player needs to have in their head when playing the game, with frequency tables for everything, and statistical analyses to make sure their findings are significant. The relative strengths and weaknesses of each option needs to be weighed. Two PhD dissertations need to be written out for any given match, one for what's going on in each player's head. If you aren't doing this, even subconsciously, while you play, you are playing the game wrong. Bad competitive players just play safe and don't think about these options, but are able to win a couple matches because they're patient. Terrible competitive players aren't even patient. Neither of these types wins tournaments. So you see, even this knowledge is a tool, and many smashers know the knowledge, but they don't know why that's important, so even if they use the tool, it's like using a hammer to make a moulding. The results aren't pretty.

Ok, so I may have gone a tad overboard with my initial stipulation. It's not so much that no one knows the fundamental system of smash. Get enough experience with the game, and most of the revelations there aren't so revelatory, after all. But players of other fighter communities still get something that a lot of smashers just don't get. They actually worry about their game's systems while playing, even the terrible players. They know that thinking about this is the key to victory. And if they lose, it's because they're just not good enough to extrapolate consistent reads from their opponent. But a good many smashers don't seem to care about that. That needs to change. There need to be more threads that actually lay out plainly what beats what, in a general sense, for a given system, and why the relationship in that system is important. This community needs to be more concerned with what the fundamentals of Smash entail. Hopefully, this essay can cause that change. Hopefully, Smashboards can finally start talking about using those hammers to drive some nails.

Cross-posted in the Brawl Boards.